When walking around the Kraków Main Square or camping in a nearby forest, have you ever asked: ‘What did this place look like in the past?’. We know we have – and we decided to dig deep, deep enough to find dinosaurs. In our search for answers, we were assisted by two researchers from the JU Institute of Geological Sciences – Dr Michał Stachacz and Krzysztof Ninard.

1Question is a series of articles by the University Marketing science communication unit, in which specialists and experts from various fields briefly discuss interesting issues related to the world, civilisation, culture, biology, history, and many more.

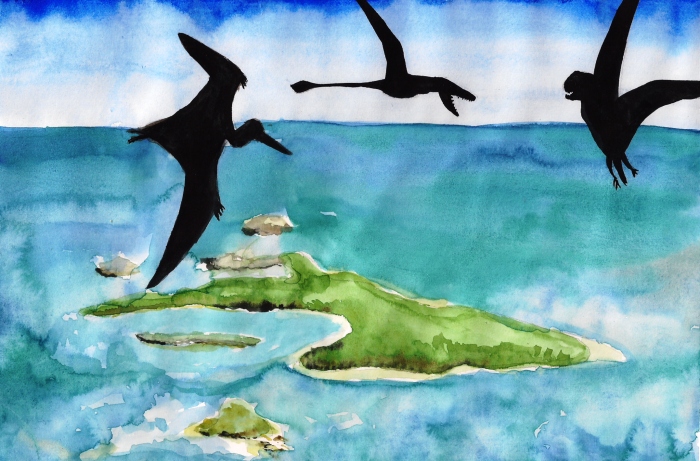

Late Cretaceous. The Kraków Archipelago

The period the Earth went through 100 million years ago can be generally called the Cretaceous, but if we want to be a little more precise, we’ll call it the Late Cretaceous, or the Cenomanian. The area known today as Kraków and its surroundings was subject to intense tectonic activity known as the Cimmerian Orogeny. It helped create the Tatra Mountains, while also deforming the old rocks underneath the area, mostly Jurassic limestone, which we can observe in the form of outcrops extending from here to Wieluń in central Poland. It formed what geologists call the Kraków-Silesia Monocline, visible today as the Kraków-Częstochowa Upland.

During the orogenetic movements happening 100 million years ago, the region was flooded by salt water several times, forming a shallow sea over the Jurassic rocks and other geological systems. We can imagine that the area was riddled with rocky islets. Periodically, the Kraków area was also an island. However, geologists are still debating whether the Świętokrzyskie Mountains, located a little more than 100 kilometres from Kraków, were elevated above the sea level or covered by the sea. Dinosaurs may have walked the nearby lands, but so far there have been no signs of their presence in the Kraków area, though the skies were probably filled with flying reptiles.

During the orogenetic movements happening 100 million years ago, the region was flooded by salt water several times, forming a shallow sea over the Jurassic rocks and other geological systems. We can imagine that the area was riddled with rocky islets. Periodically, the Kraków area was also an island. However, geologists are still debating whether the Świętokrzyskie Mountains, located a little more than 100 kilometres from Kraków, were elevated above the sea level or covered by the sea. Dinosaurs may have walked the nearby lands, but so far there have been no signs of their presence in the Kraków area, though the skies were probably filled with flying reptiles.

The shallow Cenomanian sea was teeming with life, with organisms typical for today’s tropical or subtropical areas, such as sea urchins, large bivalves, and brachiopods. The seabed was made up of sand and sometimes gravel, transported here by waves from inliers or the bedrock. The excellent living conditions were caused by a very hot climate, which in turn was the result of a high carbon dioxide presence in the atmosphere (approximately three times higher than now). In those days, the global sea level was 200 metres higher than we have today. There were also no ice ages. The sea level stayed this high (or even higher) for several dozen million years, which is proved by layers of chalk and similar rocks.

Quarternary. The Vistula glacier

The last 2.5 million years in Earth’s history, called the Quartnernary, was marked with cyclic climate changes. One hundred thousand years ago the last ice age – known as the Vistulian glaciation in Poland, Würm glaciation in Western Europe, and Wisconsin glaciation in America – had already been underway for several thousand years. Still, it was the early stage of the glaciation, and the continental glacier had not yet reached northern Poland.

The following glacials and interglacials (warmer periods) involved not only advancing and receding of continental glaciers, but also shifts in the distribution of plants and animals. Climate changes, in tandem with the fluctuations in sea level, affected the course and intensity of erosion and accumulation of sediments by flowing waters.

In the face of a few million years of environmental transformations in the Kraków area, the changes in last 100 thousand years seem subtle. The landscape wasn’t much different than what we see today. Nevertheless, there has been some degree of change, resulting in a more varied topography. The limestone rocks near the Vistula River were less exposed, since the bottom of the river valley was 10 metres higher than it is now. The area near today’s city centre was covered by a braided river with a number of small islands. Local hills, including Sikornik and Sowiniec, didn’t yet acquire their sediment cover of loess brought in by winds. On the other hand, isolated hills in the Kraków area used to be larger, but have shrunk in the last few centuries due to mining projects.

In the face of a few million years of environmental transformations in the Kraków area, the changes in last 100 thousand years seem subtle. The landscape wasn’t much different than what we see today. Nevertheless, there has been some degree of change, resulting in a more varied topography. The limestone rocks near the Vistula River were less exposed, since the bottom of the river valley was 10 metres higher than it is now. The area near today’s city centre was covered by a braided river with a number of small islands. Local hills, including Sikornik and Sowiniec, didn’t yet acquire their sediment cover of loess brought in by winds. On the other hand, isolated hills in the Kraków area used to be larger, but have shrunk in the last few centuries due to mining projects.

The plant pollen found in sediments helped determine the climate in the early stages of glaciation. The average annual temperature was 0°C, that is, about 9°C less then now. Such environmental conditions, with little precipitation, favoured plants and animals typical for boreal ecosystems. The region was covered with low birch-larch-pine forest, not unlike the ones found in today’s Scandinavia. The remains found in the Bat Cave near Ojców suggest that the area was inhabited mostly by small rodents – lemmings and mountain hares. However, larger ones, like woolly mammoths and woolly rhinos, also sought shelter there. Several sites in southern Poland featured remains of reindeers, elks and giant deer – the prey of local Neanderthals, whose presence is evidenced by flint tools and teeth found by archaeologists in the area.

Illustrations: Kinga Jastrzębska

Original text: www.nauka.uj.edu.pl