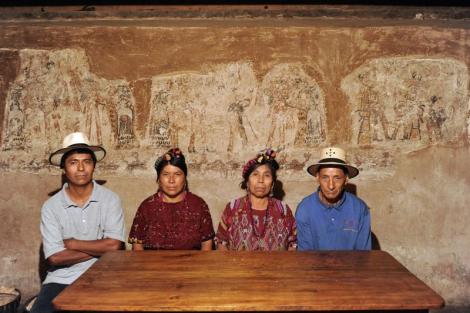

Private houses in the Guatemalan town of Chajul contain priceless wall paintings from the colonial period. They show scenes of ritual dances from several hundred years ago, combining pre-Columbian and European motifs. According to Prof. Jarosław Źrałka from the Jagiellonian University Institute of Archaeology, the old houses could have been inhabited by senior members of local brotherhoods known as cofradías, whose tasks included organisation of religious festivals.

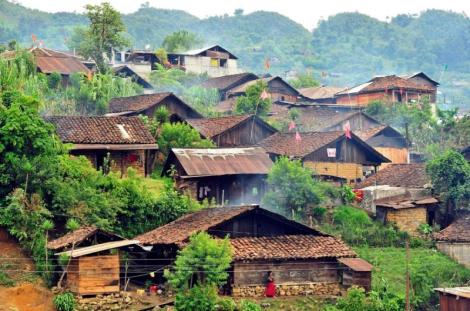

The town of Chajul is located 2,000 metres above sea level in Sierra de los Cuchumatanes mountains in central-western Guatemala. It is almost exclusively inhabited by descendants of Ixil Maya. In pre-Columbian times it already had a status of a major centre, ruled its own royal dynasty. In 1530, after the conquest, the region was taken over by Spain, which brought about a number of significant political, administrative and demographic changes. Yet, the indigenous local authorities managed to survive under the Spanish rule, and some Maya leaders became part of cofradías – religious brotherhoods founded by the Europeans, which enjoyed considerable autonomy. On the one hand they helped the Church in organising religious ceremonies, propagating Christian worship, and taking care of devotional statues used during processions. On the other hand, they preserved many elements of the pre-Christian religious tradition.

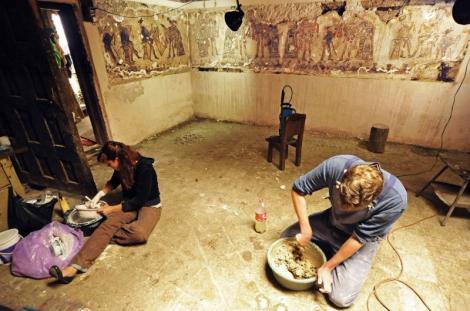

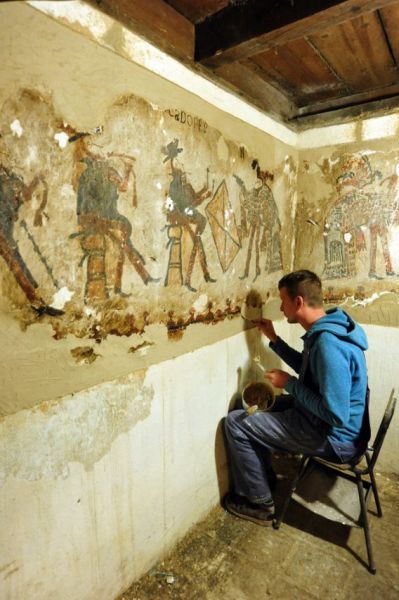

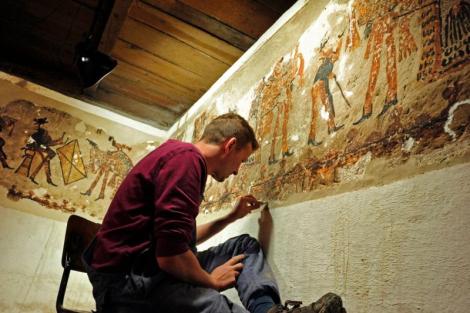

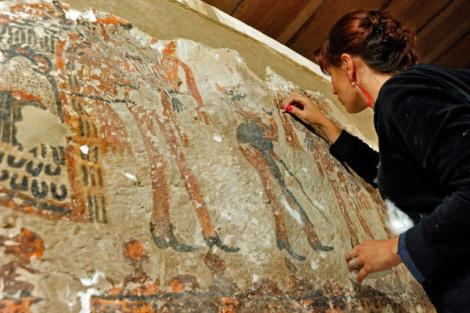

Prof. Jarosław Źrałka first visited Chajul in 2011. From a Guatemalan archaeologist Juan Luis Velásquez, who has long worked in the region, he learnt about unique wall paintings located in a private house. The researchers suspect that there could be at least 10 houses with such frescos. They were built of adobe bricks made of local clay, bound with mortar mixed with organic materials, such as pine needles. Radiocarbon dating has shown that the buildings were erected in the 17th or 18th century. The wall paintings most probably originated during the same period.

‘When I saw these wall paintings I immediately decided that it is necessary to obtain funds for the relevant research, as they are extremely rare and unique works. Many adobe brick houses disappear from the local landscape. A similar trend could be observed in Poland several dozen years ago, when people were getting rid of wooden houses. A lot of Guatemalans emigrated to the United States for economic reasons. They have been sending their earnings to their families, as a result of which, the town has undergone considerable changes in recent years. Lots of new houses are being built. One of the houses where we carried out our research survived only thanks to the efforts of our long-time collaborator, the local historian Lucas Asicona’, says Prof. Źrałka, who leads the international research team working in Chajul.

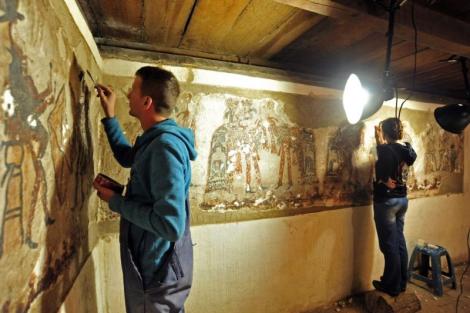

Conservation works in the town started only in 2015. For this purpose the researchers received funds from Helena Zaleska, who is of Polish origin and lives in France. Three years later Prof. Źrałka obtained a grant from the National Science Centre for the documentation, conservation and analysis of the frescos, which allowed saving these works in two more households.

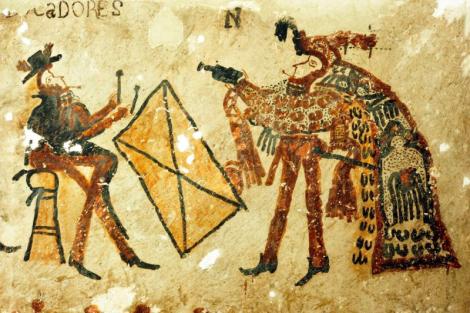

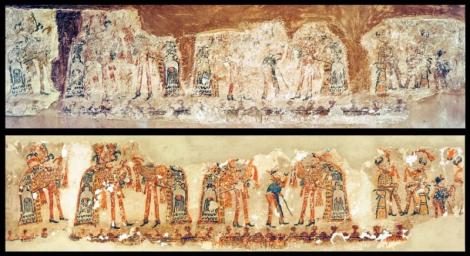

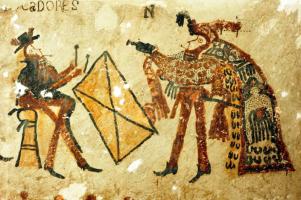

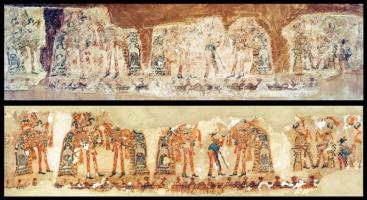

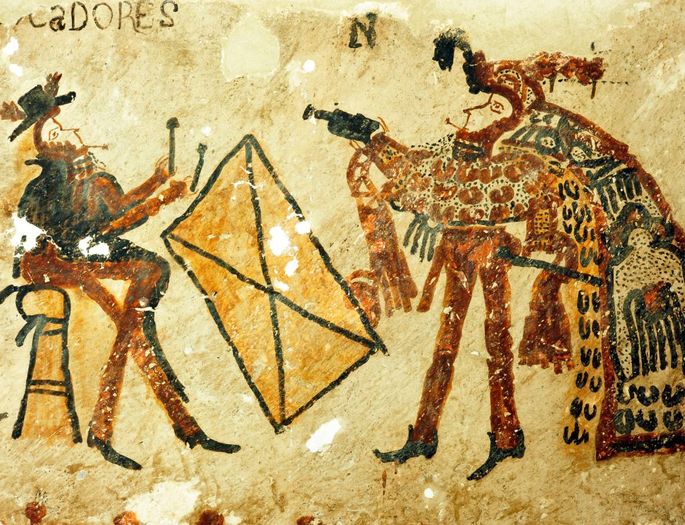

‘The paintings cannot be compared to similar works from that period decorating the walls of churches and monasteries. This art concentrated on religious themes, while the Chajul frescos show scenes of a completely different kind, such as processions of musicians and dancers in pointed shoes and rich costumes, combining European and indigenous elements. One of the musicians holds a flute or a chirimía, a wooden instrument resembling an oboe, another plays a huge drum, hitting it with sticks with rounded heads. There are also two people playing baroque guitars. Some of the individuals are shown smoking pipes, which seem to be of pre-colonial origin, as ritual smoking of tobacco used to play an important part in the Mayan culture of that period. The wall paintings also feature floral ornaments. We initially thought that they depict flowers in vases. But according to local biologists, they actually show cacti belonging to a species that produces beautiful white flowers’, explains Prof. Jarosław Źrałka.

It is almost certain that the frescoed houses originally belonged to prominent members of the local community, who belonged to cofradías, and the wall paintings were made by indigenous artists. It is very likely that they were all created either by a single person or members of a single workshop. What also suggests the artists’ native origins is the fact that their works contain pigments produced from local minerals using traditional methods, almost unchanged from the pre-Columbian era, as shown by the results of the analysis of over a dozen samples taken from the frescos conducted by experts from the University of Valencia, Prof. María Luisa Vázquez and Prof. Cristina Vidal.

‘Cofradías practiced dances. We believe that the wall paintings show the most popular of them, known as Danza de la Conquista - the Dance of the Conquest, which commemorates the conquest and colonisation of Central America by the Spanish. It has a form of a street theatre performance featuring two groups of dancers, one of which plays the role of invaders, and another of the powerful K’iche tribe. They enact a great battle between the two cultures which took place in 1524 and involved a duel resulting in the death of the native chief Tecún Umán. The frescos in one of the houses also depict women allegedly performing the Hummingbird dance, also known as the Dance of Baskets, related to wedding ceremony’, says Prof. Źrałka.

The frescos were also discovered in several other Chajul houses. In one of them they were very well preserved and protected by a plastic film, but the owners did not want the conservation works to be carried out there, so Kraków researchers were only able to document these works.

‘I am very grateful to the Maya community for letting us into their houses. Many local residents showed interest in our work. Some of them found it difficult to believe that someone could come with their own funds from the other end of the globe and work for the public good. They thought that there had to be some catch. This is perfectly understandable. The local community has been mistreated for hundreds of years by various authorities, especially during the colonial period. This part of Guatemala also suffered greatly during the civil war that started in 1960 and ended in 1996. We wanted to preserve the cultural heritage, which – in my opinion – is valuable not only to Latin America, but also to the entire world, as the wall paintings are a unique combination of European and pre-Columbian style’, adds the JU archaeologist.

The Guatemalan research team participating in the project was initially led by Juan Luis Velásquez, and later by Evelyn Búcar.