Over a hundred years ago, wonderfully preserved fossils have been found in a remote Canadian mountain range. What's particularly astonishing about them is the fascinating appearance of the creatures, which look a lot like extraterrestrials from science fiction movies. Prof. M. Adam Gasiński from the JU Institute of Geological Sciences talks about this extraordinary phenomenon.

1Question is a series of articles by the University Marketing science communication unit, in which specialists and experts from various fields briefly discuss interesting issues related to the world, civilisation, culture, biology, history, and many more.

The Burgess Shale Formation (located in British Columbia, Canada, on the Burgess Pass in the Rocky Mountains, in the Yoho National Park) was first "discovered" by the local Native Americans due to the rocks' usefulness in roofing. Somehow, some pieces of shale ended up at collectors' trade shows in the USA and Europe. The fossils in the Burgess Shale are numerous, striking, and extremely well preserved. They were described for the first time by Charles Walcott from the Smithsonian Institution in 1909. He organised a palaeontological expedition to find a site with rare specimens' remains (particularly Marella, colloquially known as the "lace crab", which was very popular amongst palaeontologists at the time). Because of their rarity, they were valued by collectors and frequently purchased for exorbitant prices. The Burgess Shale Formation was also very attractive for researchers, considering the pristine state of the fossils.

505 million years ago

The sediments which contain these fossils are layers of black and dark grey shale (30 millimetres thick on average). They are equatorial ocean sediments, probably from the slope of an underwater limestone cliff. The dark colour of the sediments suggested oxygen deficiency during their formation, which has been proven by geochemical research. Due to poor oxidiation, the fossils were well preserved, while relatively mild sedimentation (i.e. the process of falling of suspended particles in a liquid) allowed them to remain intact. During the tectonic movements in late Cretaceous (the Laramide orogeny), the sediments were uplifted, and they're now located on land.

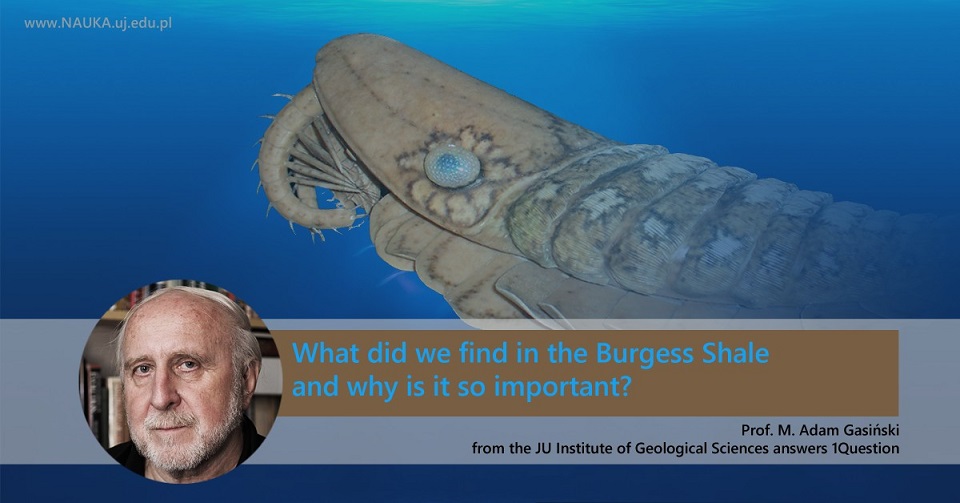

Background: Laggania, an invertebrate which probably sustained itself similarly to modern whales. Model created by Espen horn for Hessiches Landesmuseum Darmstadt and Staatliches Museum für Naturkunde Karlsruhe. Photograph: H. Zell. Licence: CC BY-SA 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons.

Photo of Prof. M. Adam Gasiński by Waldemar Obcowski.

The Burgess Shale fossils are mainly invertebrates. Their exoskeletons and limbs are very often well preserved. In some cases, this also holds true for their muscles and gorges. The internal organs of the fossilised animals are sometimes in exceptional condition as well. This is particularly astounding when we consider their age and the length of their "imprisonment" in the rock, as they can be dated back to 505 million years ago (early Palaeozoic, middle Cambrian). Since the first excavations, archaeologists have collected about 7,000 specimens from Burgess Pass. It's worth mentioning that we now know of many other similar sites – the best-known are located in China, Greenland, Siberia, Australia, and the United States. Several discoveries have been made in Poland as well.

The Burgess fauna was masterfully described and interpreted by a famous Harvard University palaeologist and science populariser, Stephen Jay Gould, in his book Wonderful Life (1989), widely recognised in the palaeological community. Since its publication, the fossils have been re-researched and re-described several times, for example in the studies conducted by Cambridge University's Simon Conway Morris (The Crucible of Creation, 1998) and Yale University's Derek Briggs.

Anomaloceris is on the hunt

So why are the Burgess Shale fossils so important? Well, first of all, they are diverse and very well preserved representatives of (mostly) macrofauna. In the middle Cambrian period, the oceans were heavily populated by trilobites, graptolites, and many other well-known invertebrates. However, their true uniqueness lies in the fact that most of them have no descendants in the modern times, or even in periods later than Cambrian (so, no descendants younger than 485 million years ago). This poses a problem to scientists (and at the same stirs their imagination), because actualistic studies are one of the methods of research most frequently employed by archaeologists.

Naturally, our knowledge has improved much since the works of Charles Walcott and Stephen Jay Gould were published, but scientists estimate that approximately 40% of Burgess Shale Formation specimens have no descendants in modern oceans.

Some of these fascinating animals are:

Some of these fascinating animals are:

- Genus Anomaloceris – a nearly two metre long terror of the deep, it had prehensile front limbs and powerful mandibles, able to tear through the exoskeletons of even the toughest invertebrates (such as trilobites). The mandibles were first found independently and thus initially have been described as an separate fossil. To this day, we haven't found the creature's descendants;

- Genus Wiwaxia – covered with barbs and scales, the taxonomic classification of this organism is still disputed: is it a mollusc or an annelid? We have found no living descendants of this animal in modern oceans;

- Genus Hallucigenia – its name was inspired by the unusual shape of its body (the researcher though he was "hallucinating"), currently classified as a onychophore;

- Genus Pikaia – classified as a chordate, it's the ancestor of vertebrates (it's worth mentioning that the Cambrian sediments contain microfossils of conodonts, which are treated as ancestors of vertebrates);

- Genus Opabinia – an arthropod with many eyes and a characteristic proboscis for a mouth. No modern descendant has been discovered.

Anyone interested in seeing more "otherworldly" creatures can do so by visiting the official Burgess Shale website.

How should we interpret the Burgess Shale fauna? We can follow the footsteps of the first researchers and regard them as a "evolutionary dead end"; we can treat the clumped fragments of various organisms as one fossil; finally, we can blame our inability to fully explain the existence of these creatures on insufficient knowledge about modern organisms (though palaeontologists don't like to think this way). We should remember, however, that even now we discover new species of plants and animals every year. Therefore, we have to recognise that we have many fossils yet to uncover, and they may prove to be the missing links between the "weird Burgess animals" and species currently living on Earth.

Watch Nature's movie on the difficulties which palaeontologists had to overcome to classify Hallucigenia, including: "Which part is the bottom?".

Photo of Anomaloceris by James St. John, CC BY 2.0, via Wikimedia Commons.

Original text: www.nauka.uj.edu.pl