‘Ships sailing in the air, or flying in the Middle Ages’ was the title of a lecture delivered by Dr Wiktor Szymborski from the JU Faculty of History on 21 October 2016 in Auditorium Maximum. The lecture was organised by the Disability Support Service, and adapted to the needs of the visually impaired and hard of hearing. In a short interview, Dr Szymborski discussed the subject of his lecture.

Łukasz Wspaniały, JU Press Office: The history of aeronautics is a very attractive field of research. It’s widely believed that the first attempts at flying took place during the Renaissance, as is suggested by Leonardo da Vinci’s sketches of flying machines. Does any chronicle contain information on whether such attempts were made in the past?

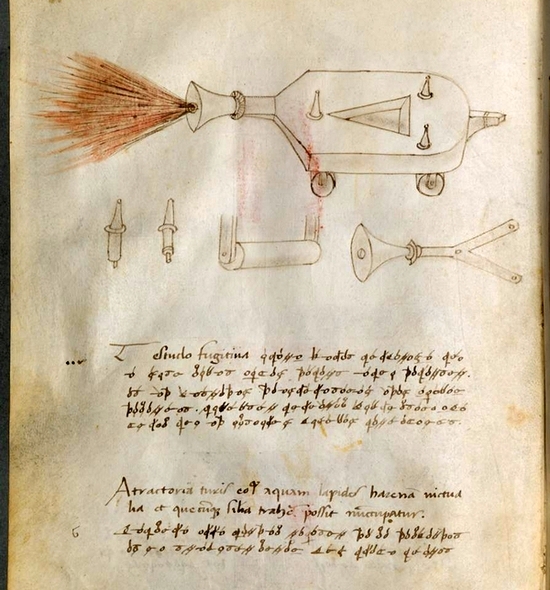

Dr Wiktor Szymborski, JU Faculty of History: It’s worth to mention that before people even thought of flying, for centuries they have been studying the wing structures of bird and bats. Villard de Honnecourt sketched flying machines long before Leonardo da Vinci – in the 13th century. We have no proof, however, as to whether anybody every built one. Many of the treatises from that period mention that people were at least planning to do so. The machine was to be propelled by human muscles.

Dr Wiktor Szymborski, JU Faculty of History: It’s worth to mention that before people even thought of flying, for centuries they have been studying the wing structures of bird and bats. Villard de Honnecourt sketched flying machines long before Leonardo da Vinci – in the 13th century. We have no proof, however, as to whether anybody every built one. Many of the treatises from that period mention that people were at least planning to do so. The machine was to be propelled by human muscles.

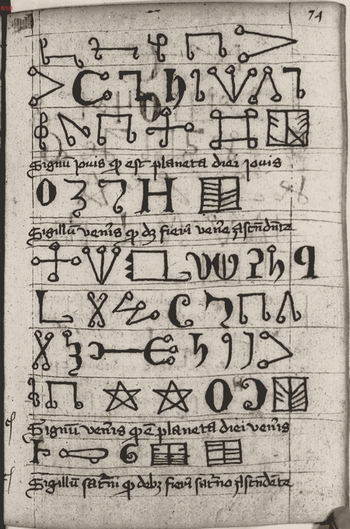

One of the libraries in Munich possesses a unique book on necromancy. What spells did the medieval magic users cast in order to rise up into the air?

The 15th century book you mentioned, resting at the Bavarian State Library, is a very interesting object. It wouldn’t have been preserved to this day if someone didn’t remove its title page and table of contents. It contains several incantations intended to allow one to fly. For the most part, they were very simple.

One of them was a spell summoning a flying black horse which would carry its rider to the skies – the mount was supposed to be a demon in the form of a steed. Another way to travel by flight was to summon a magical throne. The spell needed to be cast on a windless day in a secluded place by reciting the prayers Ave Maria and Pater Noster along with some fragments of Psalm 50 as well as drawing circles on the ground. Various powders, flour, salt, chalk, water, and fire were to be used at some point of the ritual.

The Middle Ages gave us not only aeronautic visionaries, but also the first experimenters in this discipline. Could you tell us more about these brave souls?

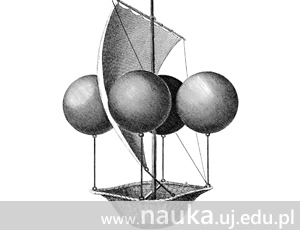

Although he was a doctor, not an engineer, Giovanni Fontana, a 15th-century thinker, dreamed of conquering the skies. He believed that the future would belong to machines with mechanical wings. What’s more, he rejected the notion of using hot air balloons for air transportation – he judged them to be too dangerous.

In the medieval times, there were many daredevils who tried to glide on self-made wings. Such attempts were made in Scotland, Venice, Nuremberg, Constantinople, Moorish parts of Spain, Khorasan (now Iran), and China.

Cross-sectional books on the history of aeronautics and articles describing tragic accidents involving great heights frequently mention a man by the name of Eilmer of Malmesbury. Why does his attempt at flying receive so much attention?

It’s undoubtedly the most important and best known person when it comes to paving the way to human flight. He was a Benedictine monk, which is surprising considering that men of the cloth were expected to pay attention to the more spiritual aspects of the heavens. Eilmer, however, was a more practical person. He strapped wings to his arms and legs and jumped off the monastery’s tower. It was a partial success. According to a chronicler from the 12th century, the monk glided over a distance of about 200 metres and then broke both his legs when he tried to land.

Eilmer of Malmesbury’s attempt is credible, since his feat was registered in a chronicle about one hundred years later. Over time, it spread around Europe and became widely known. It was even included in one of the most important medieval encyclopaedias: Speculum maius by Vincent de Beauvais. In the 14th century, as a result of an error, his name was changed to Oliver. Eilmer appeared as Oliver in Polychronicon, an important book on the history of Britain. In the 17th century, English bishop Chester John Wilkins wrote about Eilmer in his book on the first attempts of flying made by men. Finally, his story was featured in John Wise’s System of Aeronautics, one of the first and most important book devoted to flying published in the United States. It’s safe to say that the 11th-century monk became an integral part of the history of aviation.

When talking about flying in the Middle Ages, it’s also important to take into account the perception of sky and heaven. What did people think about it back then?

Indeed, chroniclers have recorded a multitude of visions of heaven and beings that inhabited it. According to folklore, air was seen as somewhat of an invisible ocean. Consequently, people saw flying machines as akin to ships sailing in the skies. This led to stories about unearthly vessels appearing out of nowhere and anchors falling down from above. This imagery was particularly prevalent in the Celtic mythology. An incident involving a flying ship was also reported in France – around 820, the bishop of Lyon scolded his flock for believing that sailors from a heavenly ship were stealing their crops and fruits.

The examples you provided are a proof of great creativity of medieval constructors. Why is this subject so rarely investigated by historians?

When I first began collecting research materials, my knowledge on the subject was very limited. I discovered this fascinating area of study during my visit at the University of Oxford. Its archives feature an extensive collection of documents describing the technical details of flying machines. There’s also a lot about the idea of human flight itself. These issues are known only to a very small group of people specialised in the history of technology. Personally, I believe they should be discussed more widely. After all, there’s no shortage of sources.

* * *

Dr Wiktor Szymborski is an adjunct academic at the JU Department of History of Culture and Historical Education. In 2009, he defended his PhD thesis Indulgence in medieval Poland. Currently, he’s researching the Dominican Order’s educational system in the Polish province. He is interested in medieval and late medieval culture, history of the Dominican Order and auxiliary sciences of history. He is a member of the Polish Heraldry Society, Society of Friends of Science in Przemyśl, and Polish Society for the Study of Religions. Last year, he received a scholarship for young researchers from the Polish Ministry of Science and Higher Education.

Photograph under the title: modern artist’s rendition of first attempts at flight. Licence: Public Domain.

Original text: www.nauka.uj.edu.pl