In early January, the information about the planned wild-boar cull in Poland provoked a public outcry. This solution was supposed to effectively prevent the spread of African Swine Fever. Prof. Henryk Okarma from the JU Institute of Environmental Sciences and Prof. Zygmunt Pejsak from the National Veterinary Research Institute have been asked to shed more light on this controversial topic.

The African Swine Fever (ASF) is a contagious viral disease that affects pigs, wild boars, and their hybrids. It’s considered extremely deadly, as the mortality in an infected herd can reach 100 percent, and can remain pathogenic for a long time. As Prof. Pejsak points out, ‘It can survive in blood for more than one year in temperature of 4° C, for several months in deboned meat, and for several years in a frozen carcass.’ Prof. Okarma remarks that ‘[the virus] is transmitted not only by direct contact between living animals, but also through contact with infected dead bodies and faeces, as well as consumption of contaminated feed or using infected straw. Pets who come into contact with pig or boar carcasses can also carry the disease.’ Prof. Pejsak adds that ‘the main problem with fighting ASF is related to the long survivability of the virus in infected carcasses lying on fields, meadows and forests for many weeks. As shown by the data presented by the research team led by Dr Klaus Depner from the Friedrich-Loeffler-Institut, Germany, it may take up to three months for dead boar’s soft tissues to fully decompose, depending on the temperature.’ The virus is easily transmitted via meat and blood.

The current costs of fighting the disease are enormous – the Polish government pays hunters 650 zlotys for killing a wild boar, whereas those who report the finding of a dead body are rewarded with 200 zlotys. Hence, the total costs can even amount to 200 million zlotys. What’s more, in a worst case scenario, Poland could even lose the right to export pigs and pork, which play an important part in its economy as there are about 10 million pigs reared in this country. It’s estimated that in 2018 the fight against ASF cost the Poles almost 30 million zlotys.

Shooting boars is not enough

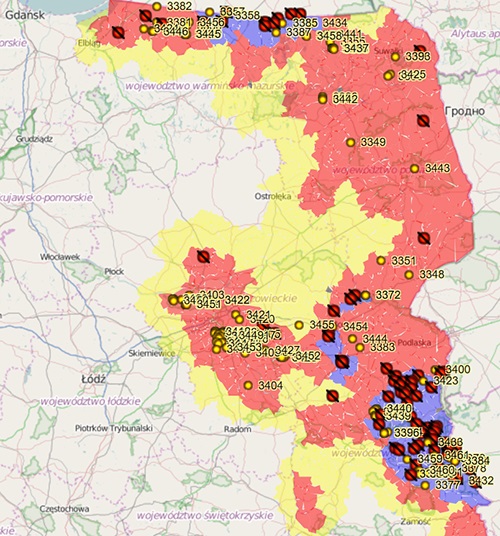

The African Swine Fever virus was first spotted in the 1920s in Kenia. It came to Europe in 1957 with pork imported from Africa. The first case of ASF in Poland was reported on 17 July 2014 in Podlasie region, which resulted in the adoption of preventive measures by the authorities. Yet, the area affected by the disease is expanding year by year. So what went wrong?

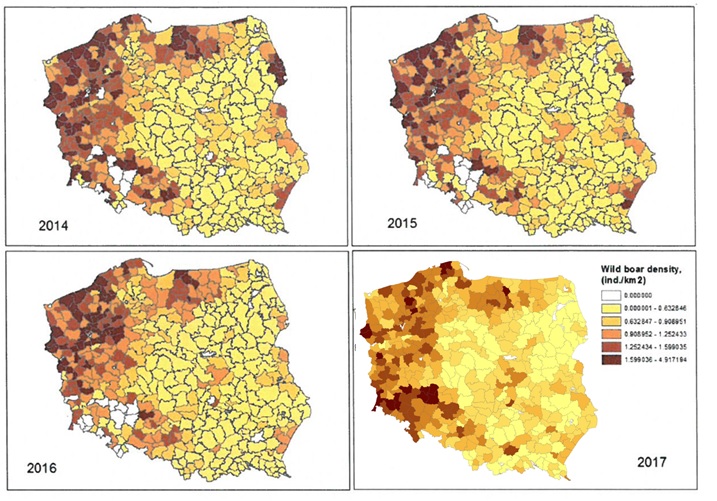

It turns out that the problem is much more complicated than it would seem, and the reduction of boar population – even if drastic – will not solve it. As pointed out by researchers from the Polish Academy of Sciences, only 5% of hunted boars are infected with the virus, whereas in the case of those which are found dead, this percentage is 16 times higher. What’s more, the exact size of the boar population in Poland remains unknown. Despite a six-fold increase in the number of wild boars annually shot in Poland during the years 1975-2015, their population hasn’t declined. Currently (in 2019) it’s roughly estimated at 300 thousand animals, but many experts think it is much higher’, says Prof. Pejsak. This can be attributed to more favourable breeding conditions, better survivability, and lack of effective control over the growth of boar population.

The problem of ASF isn’t limited to Poland – Western European countries first faced it several dozen years ago. What makes the Polish situation different, is the especially high density of boar population, which greatly facilitates the spread of disease.

According to Prof. Pejsak, ‘fighting the virus in farm animals is easy (albeit expensive). The problem starts when wild animals become infected.’ Wiping out the entire wild boar population would be very hard, partly because it’s very difficult to estimate its size, which makes the eradication (complete elimination) of the disease a painstaking process.

Biosecurity problems

An alternative way to fight the virus consists in ensuring the biological security of farms, known as biosecurity. Paradoxically, the main problem with ASF lies in humans, not boars. ‘There have been some reckless and reprehensible practices, such as bringing infected animals to pig farms, buying cheap livestock of unknown origin, letting pigs out and feeding them with slops, or even selling infected animals to other farms or burying dead pigs in the woods’, Prof. Okarma points out. The biosecurity programme implemented since 15 July 2017 includes a set of measures aimed at minimising the risk of transmitting the virus, including feeding pigs only with food inaccessible to wild animals, keeping a register of vehicles used to transport pigs into farms and persons entering pigsties, preventing access of other animals (wild and domesticated) to farm buildings, as well as laying disinfection mats at the entrances.

It seemed that the biosecurity programme would effectively stop the spread of ASF. Yet, the report by the Polish Supreme Audit Office from January 2018 indicated that the new rules have been scarcely implemented and not widely followed. The main reason is that Polish pig owners are small farmers who couldn’t afford the introduction of all safety measures. Besides, close inspections of farms began as late as April 2018, so all biosafety certificates issued prior to that date should be considered invalid. The implementation of the programme was also hindered by the lack of clarity of many of its regulations.

What is to be done?

According to Prof. Okarma, African Swine Fever can be successfully combated, as shown by Western European experiences: ‘[Western] European countries have effectively coped with ASF but the occurrence of illness led to fundamental transformations in the way pigs are reared, such as the elimination of homestead piggeries and the development of biosecured intensive pig farms.’ On the other hand, Prof. Pejsak points out that in some countries the spread of virus led to the complete abolishment of pig farming, so the problem in Poland cannot be taken lightly.

Hunting can indeed be an effective way of reducing boar population to the desired level. But the way in which boars are hunted (battue hunts), means that the animals are forced to migrate, spreading the virus to new areas. What’s more, researchers haven’t yet been able to determine the boar population density level, which can be considered safe. Besides, it is argued that in fact wild boars play a secondary role in the spreading of ASF. ‘Data from the Iberian Peninsula have indicated that the virus cannot survive long without a regular transmission between pigs and boars’, claims Prof. Okarma. In contrast, Prof. Pejsak thinks that effective combat against ASF in Poland requires a major long-term reduction of boar population.

According to the researchers, there is no single perfect solution to the problem. The strategy of fighting ASF must be well-planned and diversified. Under the present circumstances, neither a wild boar cull nor the introduction of biosecurity measures can be successful alone. Only a multi-faceted approach involving cooperation on many different levels can ensure successful combat against the disease. Biosecurity measures would be enough if adopted by everybody without any exceptions. The wild boar cull is a price that has to be paid for human error and negligence.

The article was written with the assistance of Professors Henryk Okarma and Zygmunt Pejsak.

Original text: www.nauka.uj.edu.pl