According to textbooks, the brain is divided into several parts, and each of them is used to process different types of sensory information. However, the results of a research conducted by a JU team published in the eLife journal suggest something else entirely.

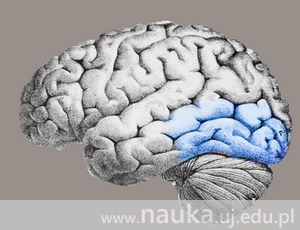

Jagiellonian University researchers have taught non-visually impaired people to read Braille. As it turns out, after several months of honing this difficult skill, changes in the brain do not happen in the part responsible for touch, but in the part responsible for sight.

"Textbooks suggest that visual cortex and tactile cortex are responsible for processing different information", said Dr hab. Marcin Szwed from the Jagiellonian University. "The results of our research have undermined this theory. They show that if we devote enough time and energy to learn a complex skill, the brain can create new neural connections which span several of its parts."

The study proves that when we learn complex skills, such as playing the piano or driving a car, we can change the neural mapping of our brains. Our effort and force of will can overcome the default information processing distribution and create new connections which increase our mental capabilities. This phenomenon is discussed in the article entitled "Massive cortical reorganization in sighted Braille readers", published in the eLife journal (open licence, CC BY 4.0). The journal publishes articles related to life sciences and medicine.

It has been known for some time that the brain adapts to new situations caused by injuries or loss of sight. For instance, the visual cortex of visually impaired people loses its original purpose, but does not stay idle. Instead, it remaps itself to assist in tactile reading and language memory. Scientists thought that it might be possible for people with normal eyesight, but they lacked proof.

It made us human

For nine months of the research, a group of 29 non-visually impaired volunteers learned to read Braille with their eyes covered. At the end of the study, they were able to read at the speed of 17 words per minute. Before and after the study, they were subjected to a functional MRI scan. It turned out that because of the research, a part of the visual cortex – the Visual Word Form Area – was activated during tactile reading. Moreover, additional neural connections have been created between the visual and tactile cortex.

This extraordinary ability of our brains to overcome their limits might be one of the things that made us human.

In another experiment, in which Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation (TMS) was employed, the scientists inhibited the activity of visual cortex. They observed that the participants suddenly lost their ability to read by touch. This points to the fact that the activation of visual cortex is not the result of imagination, i.e. it is not connected to visualising Braille writing.

"For the first time, we demonstrated that remapping on such a large scale is possible in the brain of an adult, healthy person", added Dr hab. Marcin Szwed. "We can induce changes in our brain. The results of other research suggest that our brains have much more plasticity than the brains of other primates, such as chimpanzees. This extraordinary ability of our brains to overcome their limits might be one of the things that made us human."

Original text: www.nauka.uj.edu.pl