In what times do we live? Who are the humans of today? How can they be perceived in the light of mutual influences between them and their biological environment? These issues were the common traits of two initial meetings of the Evolution Week in Kraków.

We live in an epoch when human beings can greatly interfere in evolutional processes throughout the globe. According to the scientific website of Gazeta Wyborcza newspaper, “more and more elephants are born without tusks. This evolutional shift has been caused by poaching. The animals, which have been killed for ivory for many years, have changed their gene pool.”

Can we consider this period a new epoch, with its own definition and terminology? How do evolutionary mechanisms influence humans today? Do they work at all?

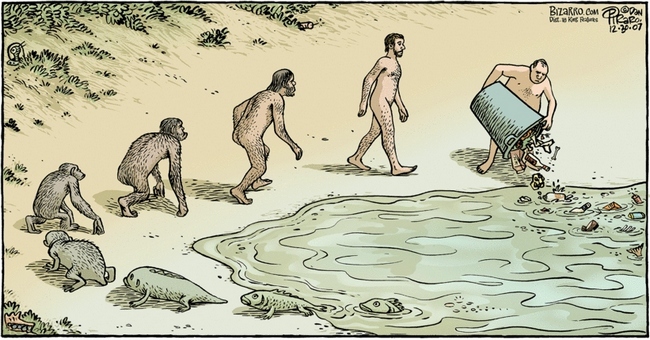

A comic vision of the evolutionary process, Dan Piraro, www.bizarro.com

These were the initial questions of his year’s Evolution Week – the key problems addressed by two eminent researchers from the Jagiellonian University: Prof. Adam Łomnicki and Prof. January Weiner.

And there came Anthropocene

The Internet is full of Anthropocene. A Google search reveals over 1.5 million results of this word. The concept has been widespread in the world of research, business and culture. In the song “Anthrocene” (a variant of the word ‘Anthropocene’), Nick Cave, an alternative rock icon, sings in a moving, apocalyptic voice: “All the fine winds gone / And this sweet world is so much older / Animals pull the night around their shoulders / Flowers fall to their naked knees.” Piano and unsettling industrial voices are heard in the background. This is only an artistic expression, yet, it illustrates the way in which Anthropocene is perceived.

Approached from another perspective, Anthropocene is only a scientific name for yet another geological epoch in the history of the world. “In ecology, it denotes what happens in the biosphere under human influence” – Prof. Weiner explains, and proceeds to list the phenomena which shape our immediate environment: “erosion and transport of sediments, the changes of biogeochemical cycles, environmental changes, the dying out of species and emergence of new ones.” This sounds relatively harmless, when compared, for instance, to the gloomy Cave’s vision.

Anthropocene

We have gained a handy concept. But it is also a sign of our megalomania, as this short period of hundreds or thousands of years can be of no importance to the biosphere.

The Polish Wikipedia explains the term as “the name for the current geological epoch, which is dominated by human activity.” Prof. Weiner addresses this issue from a similar perspective, stressing that there is no place for judgement and emotion in scientific research. After providing the definition, he discusses the timing of Anthropocene. Did it start with the utilisation of fire, with the rise of agriculture, or with the extermination of megafauna (e.g. mammoths), which preceded agriculture? But aren’t these dates too distant? It can be argued that the mass impact of humans on biosphere traces back to the industrial revolution, or, as suggested by some researchers, to the extensive use of concrete and polymers (plastics). “We have concreted a large part of the earth over, and concrete is simply a rock,” says Prof. Jan Zalasiewicz of the University of Leicester, the main proponent of making “anthropocene” part of the official scientific terminology.

Finally, the Anthropocene Working Group recommended 1950 to be officially accepted by prominent geological committees as the date when Anthropocene began. Does it have any real implications? “We have gained a handy concept – contends Prof. Weiner - but it is also a sign of our megalomania, as this short period of hundreds or thousands of years can be of no importance to the biosphere.” However, the use of a concept whose name refers to humans (from Greek anthropos, meaning human and cene, meaning “new” or “recent”) has an important informative value since it highlights possible dangers and inspires new research.

Coming back to science in the strict sense, the question arises: are we able to kill nature? Does Anthropocene also mean the end of mankind, due to global environmental changes? And maybe it marks the advent of a distinct species - a “new human”?

Prof. Weiner gives a definite answer: “The death of nature is rubbish. How can we kill nature if we are unable to properly sterilize a syringe? The humanity is incapable of destroying life on earth. In fact its power is much weaker than that of the meteorite which led to the Cretaceous–Paleogene extinction event” (when giant reptiles died out – editor’s note). “What we are able to do, is to destroy our civilization, and, as envisaged by some science fiction writers, return to living in shacks".

The biosphere will survive, whereas we – the humans – will perish sooner or later.

Too favourable conditions?

But what kind of humans will perish? Who are we and who are we going to become? Are we biologically changing, and, if so, what kind of change is it? These questions were among other important issues raised during the Evolultion Week. They were addressed by Prof. Łomnicki who asked himself the vital question: “Has our evolution stopped?”.

“Genetic changeability is the basis for all biological changes. The gene pool is influenced by selection and mutations”, explains Prof. Łomnicki. In other words, the shape of upcoming generations is determined by mutation, that is the errors that occur during reproductive cell division, and selection, which is illustrated by the aforementioned vanishing of tusks among elephants.

“Our life has never been so comfortable!”

We are still unable to influence the mutation process, which, by definition, is random and hence difficult to control. So let’s take a closer look at the selection process. The basic way to measure its force in a human population is to look at the mortality rate. Only an individual who lives to a certain age has a chance to produce offspring and pass his or her genes to the following generation. According to Prof. Łomnicki, in 1885, 46% inhabitants of Germany did not live to the age of 30. Most of them had no chance to reproduce. In contrast, 123 years later (in 2008), it was only 1.5%. Quite a remarkable change!

In the developed countries, natural selection comes to a halt. Consequently, the human capability to adapt to new conditions decreases, which is probably the crucial element of the evolutional puzzle. The effects of natural selection - the elimination of the unfit and promotion of the most adaptive to change - have been replaced by medical progress and high comfort of living. “We are living in the best times so far. Our life has never been so comfortable”, contends Prof. Łomnicki. Yet, from a global perspective, this also has negative consequences. We are losing our adaptive capabilities. From this arise questions about the pace and universality of this downfall – is it already visible, or will it become visible only when the living conditions deteriorate?

Post-humans

The weakening of natural selection has also other consequences. One of them is the erroneous view that many deadly diseases did not exist in the past. How does this relate to natural selection? In Prof. Łomnicki’s opinion, the relationship is very easy. In the past, people rarely lived to an old age, when they are especially prone to cancer as their body becomes less resilient and the vitality of their cells decreases. According to the Polish National Cancer Registry, between 2011 and 2013, the cancer incidence rate in Poland was 700 per 100,000 in the 40-44 age group. At older age, the incidence rate grew rapidly and was as high as 2,500 per 100.000 among people aged 50-54.

“We owe our greatness to the relatives of our ancestors who were failed projects and died childless”, says Prof. Łomnicki. To illustrate the current paradoxes, he refers to the concept of William D. Hamilton, best known for his theory of kin selection. This British evolutionary biologist also formulated the idea of a planetary hospital which holds that the more medicine cares over people, the greater the number of those in need of medical care becomes, and hence more money has to be spent for medical development. Medicine has replaced natural selection and adaptation to changeable living conditions.

This new human being, typical of high Anthropocene, is someone different than Homo sapiens thousands or even hundreds of years ago. Hamilton’s planetary hospital seems to lead us towards genetic engineering. “Our genes are largely a legacy of the Paleolithic, but the living conditions are utterly different”, contends the JU researcher, which corresponds to the forecasts made, for instance, by Francis Fukuyama in his book Our Posthuman Future.

***

Where does the reflection upon Anthropocene and biological evolution today lead us? These phenomena are surely strongly interrelated and intertwined with each other. One can only wonder why no researcher dealing with the definition of Anthropocene has yet suggested to define it in terms of an epoch in which the biological evolution of humans comes to a halt and a long-living post-human being is born, shaped by advances in medicine and other disciplines.

Original text: www.nauka.uj.edu.pl