From the clash of Polish nobility culture with the western lifestyle to the issues related to hygiene, cuisine and relations between genders – Dr Katarzyna Kuras gives us a peek into chambers, ballrooms and gardens of the Polish aristocracy of the 17th and 18th century.

Dr Katarzyna Kuras from the JU Institute of History specialises in the history of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth in the 17th and 18th century and the courtly life in Europe. Part of her research has been focused on August Czartoryski, a Polish magnate who was the architect of his family’s rise to power. She is currently writing a book about queen Maria Leszczyńska’s Court.

Piotr Żabicki: On 17 June 1696, king John III Sobieski died in Wilanów. Can his death be considered an event marking the start a new epoch in terms of culture, customs and lifestyle?

Katarzyna Kuras: It certainly marked the beginning of a new political epoch – the rule of the House of Wettin and Stanisław August Poniatowski, a time of a great crisis of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth which ended with its final collapse in 1795. In contrast, the changes in the area of culture and customs are evolutionary processes, instead of rapid shifts.

Korneli Szlegel: Polonaise dance

The period of late 17th and early 18th century was dominated by the ideology of Sarmatism. All cultural change was based the traditional Polish culture, characterised by the love of the past, the praise of abundant and peaceful life, and the sense of uniqueness of the Polish nation, which was reflected in numerous cultural phenomena, including the idea of Poland as antemurale christianitatis - the bulwark of Christendom.

A famous old Polish proverb says that “a nobleman at his farmstead is a voivode’s (provincial governor’s) equal”. This motto illustrated the uniqueness of Polish nobility in Europe. Obviously, everybody was aware of sharp economic inequalities within its ranks, but in the political sphere all Polish nobles had the same rights and responsibilities, unlike Western Europe, where various groups within aristocracy usually enjoyed different privileges.

And what about the 18th century?

Things certainly changed a lot. The magnates and the rich Polish nobles became more eager to draw from Western European influences. This change owed much to the Polish-Saxon union. From 1697, Poles who resided in Dresden witnessed the splendour of Saxon rulers, which was untypical of Polish tradition. Another important source of new trends was Versailles. The realities of the French court became familiar to Polish nobility thanks to the ex-Polish king Stanisław’s Leszczyński, who resided in France along with a number of Polish nobles, including members of Tarło and Jabłonowski families, who brought French fashions to the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth. The goods imported from France included cloth, wine and culinary novelties. The third source of Western influence in the 18th century was England. The fascination with this country largely stemmed from the admiration of the English notion of freedom, which differed from the Polish one. Stanisław August Poniatowski was himself a great admirer of the English culture.

Was the Polish magnate class equal to its French Italian counterpart? Was it similar in terms of wealth, customs and lavishness?

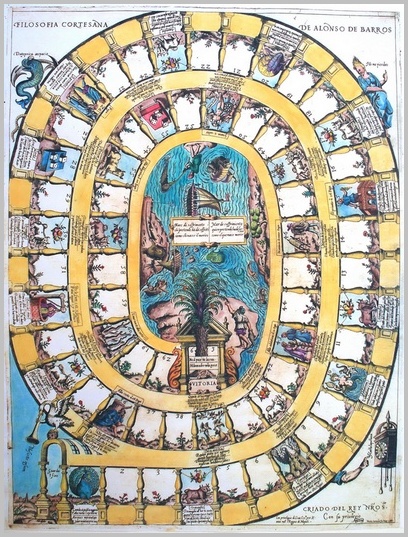

Filosofia cortesana, source: fleurtyherald.wordpress.com

The mores of the epoch that started from Jan III Sobieski’s death were more European and cosmopolitan than before, which corresponded with the Enlightenment philosophy. Beyond any doubt, Polish magnates of the 17th and 18th century were part of the European elite – they were welcome and treated as equal partners at German, French and Spanish courts. For instance, guests from Poland visiting Versailles during Louis XIV’s reign were enchanted by the Sun King’s entourage and fascinated with the differences from what they had been accustomed to, but didn’t feel overwhelmed by the wealth or by the strangeness of culture they encountered.

Polish or foreign attire?

Were there any popular ways in which nobles from different parts of Europe, including Poland, could mix with each other?

Members of elites met on various occasions. Hunting was a typical entertainment bringing together European aristocracy. Some preferred traditional hunts in the wilderness, whereas others, including, most probably, king of Poland Augustus III and Spanish monarch Philip III, hunted in a pre-arranged scenery, where mass killings of trapped animals took place.

Board games were also popular with nobility. A good example is Filosophia cortesana by Alonso de Barros, which took Italian, Spanish and French courts by storm in the 17th century. Dining and feasting was also an important part of aristocratic culture. The etiquette was largely dependent on the current fashion, a good example of which is the emergence of the fork, which became widely used in various parts of Europe in the 17th century.

Portrait of Stanisław Anotoni Szczuka by an unknown artist.

Yet, it should be pointed out that some customs were closely linked to the realities of certain countries and geographic regions. Religion was also an important factor, e.g. Polish magnates paid much heed to Catholic festivities and customs related to them.

In his work entitled Description of Customs during the Reign of August III, the 18th-century Polish historian and diarist Jędrzej Kitowicz described how magnates imitated the king’s clothing style, stating that at the end of August III’s rule only a tenth of senators and royal officials wore Polish outfit and a half of all nobles were dressed in German attire. To what extent did the foreign fashion influence how Poles dressed?

Clothing signified social position, group membership and even political allegiance. In the 16th century, when Sigismund II Augustus wanted to manifest his support towards the executionist movement, he attended parliamentary sessions in Polish attire, instead of Italian one, which he wore on everyday basis. In the 18th century, clothing became a subject of debate, which was widely documented by diarists. King Stanisław August Poniatowski was strongly criticised when he attended the coronation ceremony in a Spanish outfit instead of a traditional Polish one. It was stressed that on such an occasion even Augustus III, who came from Saxony, wore kontusz (a traditional outer garment of Polish nobility), whereas Poniatowski, born in the Polish-Lithuanian commonwealth, didn't do this.

As mentioned above, the expansion of Western European, especially French, fashion was undoubtedly one of the subjects of a public debate during Stanisław August Poniatowski’s reign. The Kontusz stood for everything that was Polish, whereas the tailcoat was associated with foreign influences.

Inspiration with foreign models must go hand in hand with information flow and travelling. However, Polish magnate is often associated with a lazy landlord, who is reluctant to leave his property and does most of his business through courtiers.

It needs to be remembered that the early modern European reality, which we are talking about, was a time of poor roads and high travel costs. Sending or receiving a letter could take several weeks. 17th and 18th century life had its own pace, completely different from what we are used to nowadays.

Magnates’ estates in 16th/17th century Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, license CC BY-SA, Wikimedia

Another factor was related to the fact that Polish magnates couldn’t afford too static lifestyle, mainly because of the necessity to govern large estates located in different parts of the country. In these days subjects had to be overseen directly and personally. Hence, magnates who cared for their property had to travel a lot. A good example is a late 17th-/ early 18th-century aristocrat Elżbieta Sieniawska, who regularly visited her estates located in several provinces. There were many magnates who behaved likewise.

Mobility and interest in the world were also stimulated by the way in which political goals used to be achieved. Appointment to an important office was often dependent on the loyalty and commitment to the monarch displayed during personal visits. Besides, those who wanted to influence state and local politics had to travel to parliamentary sessions. Such travels provided an occasion to buy various goods and hear the latest news.

The challenges posed by the world made the model of a “lazy aristocrat” no longer relevant. Magnates were often accustomed to travelling from childhood. For some Polish nobles the first serious journey was an educational grand tour of Europe, during which young aristocrats were expected to gain basic knowledge about the continent, learn foreign languages as well as basic social and cultural etiquette. Such journeys were undertaken by a number of important figures, including Jakub Sobieski and his sons: Marek and Jan (the future Polish king).

Original text: www.nauka.uj.edu.pl