Here’s the second instalment of our series on the lifestyle of Polish magnates. In this part, Dr Katarzyna Kuras talks about the social status of women, riding in coaches, terrifying vapours, and… traps in hair.

<< Back to part one

Continue to part three >>

Lords and ladies

Piotr Żabicki: The world of Polish aristocracy was a patriarchal one. However, we do know of women from that age who actively participated in cultural and even political life. What was the overall status of women?

Dr Katarzyna Kuras: It was definitely a patriarchal reality, one dominated by men. This is confirmed by the writers of that time. Andrzej Frycz Modrzewski, a Renaissance scholar, humanist and theologian, was of the opinion that women should restrict themselves to managing the household, and any man who consulted them publicly should be ashamed of his weakness. Stanisław Dunin Karwicki, a politician and political writer, shared that view, but was even more straight-forward: he wrote that ‘men are more dignified than women’, because it’s the men who worry about continuing their bloodlines and protect the kingdom during times of war.

In the 18th century, Prussian king Frederick the Great famously said that politics has fallen into women’s control: they plotted and schemed to decide the outcome of every situation, while their husbands engaged in drunken revelry. According to Władysław Konopczyński, a historian and Jagiellonian University professor, author of the book Kiedy nami rządziły kobiety [When we were ruled by women], Polish women got into politics when men were not up to the task (or, as bluntly said by Konopczyński himself, ‘when they were incompetent or thoughtless’). So, although we know that some women were active in politics, they were ultimately forced to act within the boundaries set by men.

Could you provide an example of that?

Certainly. In the last years of king Augustus III of Poland’s reign, Maria Amalia Mniszech, daughter of Heinrich, count von Brühl, a Polish-Saxon statesman, minister and diplomat, and wife of Jerzy August Mniszech, Grand Marshal of the Crown, attained an unprecedented position in politics. It took her a lot of time and effort to gain that kind of clout. First, she acted as an intermediary between her ailing father and the king. During her time at the court, she won the trust of key politicians and participated in numerous council sessions. Duchess Maria Antonia of Bavaria even went so far as to say she was preparing to become the prime minister. However, these ambitious plans were thwarted by the deaths of king Augustus (5 October 1763) and his prime minister (28 October 1763).

There are many other politically active women in our history: Katarzyna Kossakowska, Joanna Lubomirska, and Urszula Lubomirska – just to name w few.

Was it possible for women to free themselves from men’s rule? What was the situation of single mothers in that time?

The rules were very strict in that aspect. According to Wacław Uruszczak, a Jagiellonian University professor and lawyer specialising in the history of law and canonical law, woman, despite reaching the age of majority, ‘could not engage in any legal activity without the express permission of her father, adult brother or husband’. Still, women’s financial situation was safeguarded through various forms of dowry. Widows held a special position, as they were allowed quite a lot of freedom. The most notable of them were Elżbieta Sieniawska and Anna Radziwiłł.

Nevertheless, it’s very difficult to imagine a single mother being looked at with approval. The financial situation of such women would be tough, since the patriarchal society of old Poland and its laws did not allow single women to make their own decisions. Of course, it doesn’t mean that women were not protected by law at all. For instance, the marriage of Hieronim Florian Radziwiłł and Teresa Sapieha was annulled due to the husband’s difficult character. However, that case was untypical, because Teresa Sapieha came from an influential Lithuanian family, and Hieronim Radziwiłł was happy about the whole affair, since he was already planning his next marriage with Magdalena Czapska.

One more thing: only a few women from powerful families were active in the cultural and political world. Most of them were content to be wives, mothers and homemakers.

How did people approach the issue of sexual promiscuity? Was it something common?

This area was never a subject of an individual study, since there are very few sources left. Some memoirists, like Jędrzej Kitowicz, recorded gossips about people leaving ballrooms and going on a ride in a coach. This type of information can’t be regarded as reliable, and so they can’t be used to deduce the society’s moral condition.

The then-prevalent idea of Sarmatism put a lot of weight on faithfulness and harmonious marriage, and all instances of going against these virtues were frowned upon. It doesn’t mean that nobody cheated, but when they did, it was carefully and quickly covered up. Sometimes it’s difficult to tell whether someone really had marital problems, or if it was just a recorded gossip. This is true in the case of the supposed affair between Elżbieta Helena Sieniawska and Francis II Rákóczi. Even if it happened, at some point it ended and the contrite wife returned to her husband.

Things were a little different at the king’s court, particularly during the reign of Augustus II the Strong, who frequently cheated on his wife, Christiane Eberhardine of Brandenburg-Bayreuth. He had a great number of mistresses: Maria Aurora von Königsmarck, Anna Constantia von Brockdorff, Marianna Denhoff – the list goes on.

As a side note, we know much more about sexual promiscuity amongst peasantry, since this subject was studied by Tomasz Wiślicz. It turns out that both lowborn men and women were punished for extramarital affairs.

The concept of morality was strictly tied to religion. However, various folk superstitions, both regional and pan-European, were also prevalent during the time we’re discussing. In your analysis of the description of the wedding of king Augustus III of Poland and Maria Josepha of Austria (1719), you mentioned that the festivities featured a celebration of the Sun. How did people reconcile Christianity, pagan rituals (like balefires) and their admiration for ancient mythology?

I think that the syncretic and rich culture of old Poland offered ample opportunities for such contradictions. Pagan rituals have always had their followers. The fact that the peasants were Catholic didn’t automatically mean they completely abandoned all of their superstitions or witchcraft. A classic example of that is white magic – a way of explaining many natural phenomena, including herbal medicine.

As far as mythology is concerned, it’s really simple: when ancient culture was rediscovered during the Renaissance, Greek and Roman mythology, art and literature became an integral part of the European cultural heritage. Mythology provided a wonderful setting for the deeds of monarchs and military commanders. For instance, Louis XVI of France liked to be compared to Zeus or Hercules to demonstrate his greatness to his subjects. The symbolism of mythology was excessively used in politics and propaganda.

Ingenious hairstyles

The magnates wore marvellous clothing, lived in luxurious mansions and organised spectacular events. What about everyday activities, such as those related to personal hygiene?

There’s no easy answer to that question. Although in the 15th and early 16th century washing oneself was a common practice (there were many public bath-houses), it changed over several decades because of ‘new medical discoveries’. According to them, the body was protected by a natural barrier. Removing it could result in dangerous vapours entering the organism and causing disease – and, in turn, an epidemic. Therefore, frequent washing was considered detrimental. It was replaced with regular underwear change.

At the turn of the 17th and 18th century water gradually ceased to be perceived as dangerous. People started appreciating water’s beneficial influence on health (such as hydrotherapy). First bathrooms were introduced in magnates’ homes, even though a century ago they were seen as a threat to one’s life. In 1626, an architect by the name of Louis Savot wrote that ‘unlike the people in ancient times, we can do away with frequent baths, as we have underwear, which makes personal hygiene easier and more comfortable’.

So in the 18th century there was no need for powders and perfumes?

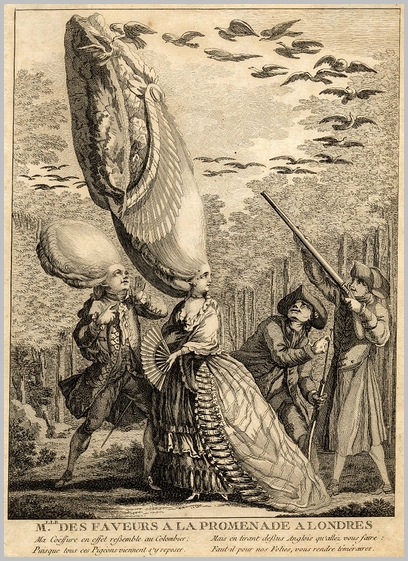

No, they were still used. Although people stopped being afraid of water, they didn’t wash themselves as often as we do nowadays, so they still needed fragrant perfumes and powders to mask other, less pleasant odours. Exquisite clothing and fancy hairstyles did not make things easier. Even the rich had to find ways of dealing with getting rid of lice and fleas. Women put small traps in their hair to deal with the insects. They also hung small mallets on their necks to crush them.

All of this was very common. We’d probably have much difficulty with tolerating the smells prevalent in the 18th century, but it wasn’t anything out of the ordinary for the people that lived back then. You just got used to it.

Let’s go back to Jędrzej Kitowicz for a bit. In his memoirs, he enumerates various dishes served at the aristocrats’ tables. Nearly all of them are meat-based. It seems that our ruling class was far from the contemporary minimalism and popularity of vegetarian food.

Vegetarian dishes may not have been as popular as they are today, but old Polish cuisine wasn’t all about meat. Kitowicz exaggeration is a stereotypical one: he suggests that the magnates were rich enough to afford eating a lot of it. However, old Polish cuisine couldn’t have been entirely based on meat due to frequent fasting imposed by the Catholic Church. There were several dozen of such days every year, and during that time it was forbidden not only to eat meat, but also cheese, butter and eggs. Because of that, the menus had to be as diverse as possible. In the case of wealthy people, that meant mostly adding a lot of lavishly prepared and served fish. A lot of popular recipes aimed to make the fish dish feel ‘meaty’. Sumptuous meal also included soups and fantastic desserts – the latter were often fruit prepared in such a way that they didn’t lose their natural shape and colour. This flair for illusion permeated the entire old Polish cuisine and manifested itself in various ways: for instance, capon in a flask was just the skin of a rooster stuffed with groats.

<< Back to part one

Continue to part three >>

Original text: www.nauka.uj.edu.pl