In the last part of the interview about the lifestyle of Polish aristocracy, Dr Katarzyna Kuras talks about the Polish queen of France and her children, freedom at the royal court, the 18th-century celebrities and... Queen Marie’s jam.

From queen’s perspective

Piotr Żabicki: In your article about privacy at the court of Queen Marie Leszczyńska (Polish King Stanisław’s daughter, who married King of France Louis XV), you did not mention spending time with children. Could that reflect some sort of coldness or even aversion to children?

Marie Leszczyńska, Queen of France, Reading the Bible (1748)

by Jean-Marc Nattier

Dr Katarzyna Kuras: Leszczyńska as a mother was frequently assessed from the perspective of her infrequent contacts with children. For economic reasons, the younger girls were sent to Fontevraud Abbey and dauphin Louis Ferdinand stayed in Versailles with three sisters. Yet, it is rarely noticed that these days the queen’s behaviour was typical of the person of her position, who had to follow courtly etiquette, which didn’t allow spending much time with children. For a long time, her only source of information about the daughters she had to part with were letters. On 28 September 1744, one of them – princess Therese – died at the age of eight. Queen Marie received the news about her death as late as October 3. The queen informed her husband about their loss in a letter. She was deeply affected by this tragedy and tried to console herself with the thought that her child had already found happiness in heaven. Some historians accused the queen of light-hearted attitude towards this death and not providing any emotional support to other daughters staying in Fontevraud. It was very difficult to maintain the bond with children who lived so far away. In 1747 Jean-Marc Nattier was commissioned by Louis XV to paint portraits of the princesses. Then the king presented the pictures to his wife – this was the first time she had “seen” her daughters for eight years.

No wonder that when the princesses came back to Versailles they were unable to establish a true relationship with their mother. Their bond with their father seems to have been much healthier. If any of Leszczyńska’s nine children had a closer relationship with their mother, it was her son Louis Ferdinand, who shared her system of values and religious views.

In the above mentioned article, you have wrote that Charles-Philippe d’Albert de Luynes noticed that it was Leszczyńska who enjoyed a level of freedom and independence previously unheard of in Versailles. How should it be understood? Marie Leszczyńska was one of the most important persons in the country, so it would seem that her freedom should have been unconditional and almost unlimited.

The Palace of Versailles (1668) by Pierre Patel

In a world governed by the rules of etiquette and ceremonial there was no such thing as unconditional and unlimited freedom. Although the queen lacked real power, she played an indispensible part in the spectacle of king’s majesty. She participated in various official ceremonies and had to bear in mind that her behaviour and gestures were public in character, as she was part of the king’s entourage.

Accordning to Monique Cottret, the author of a book about queens of France from the early modern period (Reines de France, 2015), the ideal queens were those who were apparently the most passive in the political sphere: the wife of Louis XIV Maria Theresa of Spain and Marie Leszczyńska, Louis XV’s wife. Both of them, seemingly invisible in grand politics, were well versed in courtly affairs and perfectly fulfilled their duties.

This was a world only apparently controlled by king and queen. Actually, members of the royalty moved within the framework set by their predecessors, from which they couldn’t easily break away. The 18th century is often considered the age of “privatization” of royal family life. Marie Leszczyńska had her own apartments and her own passions, which wasn’t possible in the case of Maria Theresa of Spain. And the next king’s wife, Marie Antoinette, went much further in living by her own rules, which was reflected in her notorious breaches of courtly etiquette, spending enormous amount of time with friends, late motherhood, and constant interference in politics.

According to some historians, when king and queen focused on their private and family life, they no longer appeared special and inaccessible to their subjects and lost much of their majesty. Can it explain the ease with which the royal family was disposed of during the French Revolution? Maybe.

Celebrities and queen Marie’s jam

Michał Fryderyk Czartoryski by Louis de Silvestre

Today, it's the pop culture, including television, music and celebrities, which is the vehicle of trends and fashions. And what played such a role in the 18th–century Poland?

Every ruler was a celebrity. This is especially relevant in the case of Augustus II the Strong – the ruler who impersonated bravery and daring – virtues greatly valued in Poland. Stanisław August Poniatowski took great care of his propaganda image. He did that very effectively, as we still remember his achievements in the field of education and culture, believing that they helped the Polish nation survive the long period of foreign rule.

Unique individuals valued by the nobility for different reasons were also celebrities. For instance, Michał Fryderyk Czartoryski became famous for his ability to recognise the faces of a very large number, probably several thousand, of his fellow noblemen. And Wojciech Szamocki became a “celebrity” due to his uncompromising stance in the struggle against “Familia” political party.

Are there any customs or tradition from the period of the Saxon dynasty rule in Poland (1697–1763) which have survived to the present day?

I don’t think there are many cultural patterns characteristic for that period only which have survived for so long. There certainly remained at least two popular sayings originating from the political reality of the Saxon dynasty rule. Besides, it was the period when potatoes, which are now an integral part of Polish cuisine, became widespread in Poland.

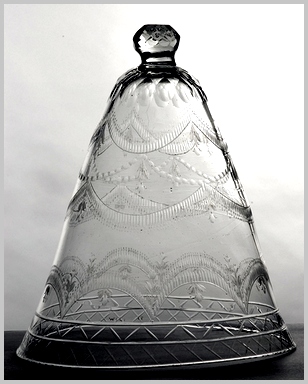

– a chalice that couldn't be put away until empty,

Wilanów Palace Museum collection. Photo by Z. Reszka.

I find it difficult to give examples of positive influences from the Saxon dynasty era. In fact, only negative phenomena come to my mind: the pursuit of self-interest in political life and lack of a serious discussion about national affairs seem to be a common denominator between the rule of both Saxon kings: Augustus II and Augustus III and the contemporary Polish politics. Another similarity between the two eras is the inability to reach out beyond partisan divisions. This flaw was the reason why most parliamentary sessions during Augustus III rule (1733–1763) were broken up.

We began with John Sobieski, so our last question will also be related to this king. Did his wife, Marie Casimire, really produced jam for her husband herself? In their correspondence there is a passage: “I’ve got fruit which I haven’t yet cooked since I don’t have an oven and a syrup.

It’s difficult to say but I am sceptical of the assumption that Marie Casimire made culinary delicacies for her husband herself. The phrase “I haven’t yet cooked” rather means “I haven’t have them cooked yet” and is probably simply a stylistic device aimed at stressing the intimacy between the writer and the addressee of the letter. Mentioning a confectioner would spoil the effect, although, most possibly, it was him who was in charge of the cooking.

Original text: www.nauka.uj.edu.pl