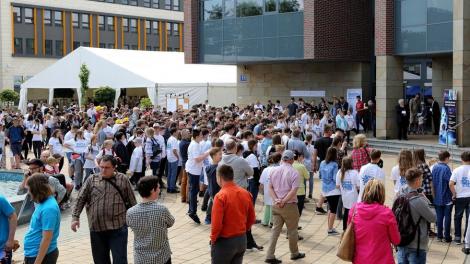

Once again, the Chain Experiment contest will allow each and every one of its participants to become brilliant inventora. True to its core principle – ‘learning through fun’ – the sixth edition of the contest will have its finale on 9 June 2018 at the Faculty of Physics, Astronomy and Applied Computer Science and will undoubtedly be attended by scores of physics-loving construction enthusiasts.

So what’s the deal? Why does the Chain Experiment bring together dozens of competing teams and a crowd of onlookers every year? We asked this question to Daniel Dziob, a PhD candidate at the JU Institute of Physics and one of the Experiment’s organisers, and Dr Katarzyna Dziedzic-Kocurek, a JU physicist and a member of the Experiment’s jurors.

‘We've “imported” the idea for the contest from Slovenia’, said Daniel Dziob. ‘As it turned out, people in Poland were just as enthralled with the mix of physics, entertainment, creativity, and tinkering. Maybe it’s because there’s no “right” way to solve any problem. There’s a great many of them, and the one common thing all the Experiment’s participants have is that they love to build, create, and explore the unknown. That and fun-loving personality, of course’.

‘We've “imported” the idea for the contest from Slovenia’, said Daniel Dziob. ‘As it turned out, people in Poland were just as enthralled with the mix of physics, entertainment, creativity, and tinkering. Maybe it’s because there’s no “right” way to solve any problem. There’s a great many of them, and the one common thing all the Experiment’s participants have is that they love to build, create, and explore the unknown. That and fun-loving personality, of course’.

Registration to the competition lasts until 31 March. After this process is complete, the organisers will send the participants small metal balls so that they may begin their work.

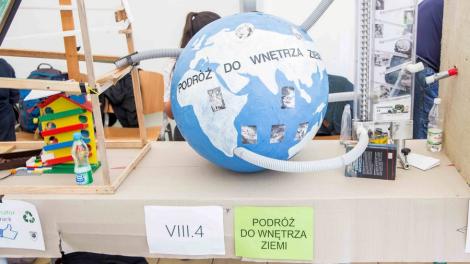

The Chain Experiment challenges the teams to build devices that transport the ball from one place to the other using the largest number of physical phenomena possible. There are no age restrictions – imagination, time, and space are the only limiting factors. During the grand finale, all devices will be connected, forming one spectacularly long chain that will be restarted several times.

The contests educational aspect is obvious: it encourages people to use their imagination and creativity while at the same time teaching them about the laws of physics. It also offers a chance to spend some time in an entertaining and creative environment, developing interpersonal skills.

The device mustn’t occupy space larger than a standard school desk, and the ball has travel through it within the time span of 20 to 120 seconds. The jury awards point for the number of physical phenomena used in the device, a clear explanation of those phenomena, the device’s complexity, the team's inventiveness, and visual appeal.

To the Bat Cave!

Dr Dziedzic-Kocurek pays particular attention to that last feature. ‘You can see that some teams have spent weeks perfecting not only the functional, but also visual aspects of their creations. We also have projects that evolve from year to year, like “The Bat Cave”. There were already two versions of this project, and we’re currently waiting for the third one. It refers to the famous Bat Cave in Ojców National Park near Kraków. Additionally, we’ve seen some devices made exclusively out of refuse and recyclable materials’, she explained.

‘Every device needs to have a name and a corresponding appearance’, added Daniel Dziob. ‘The creativity of the teams knows no bounds. I’ve once seen a detailed diorama of the Kraków Barbican. I’ve seen a number of “Star Wars” references. During the first edition, there was a device called “Winter Olympics” with hockey player figurines inside it!’.

Every project is unique, and each year the jurors are surprised with something new. ‘There was a group of students whose device’s subject was mathematical analysis. There was another one in which a jar full of honey and table tennis balls rolled down a slope. It turned out that if you combined these elements in a correct way, the jar “leaped” like a frog. And I’ve also seen some impressive constructions made by pre-schoolers out of blocks’, said Daniel Dziob.

The teams are divided into categories of varying ages. Each of them gets a separate. The physical phenomena used in the devices are chiefly determined by the participants' age: ‘Naturally, the youngest participants use things they know best from their everyday lives: slopes, lifts, levers, and spinning wheels. The older they are, the more things they’re able to incorporate in their projects. There’s electricity, magnetism, optics, hydrostatics, hoists, Gauss guns, lasers, syringes, pistons, and so on and so forth’, explained Daniel Dziob.

‘It’s also worth to mention chemical reactions that appear in some of the more advanced projects’, added Dr Katarzyna Dziedzic-Kocurek. ‘Obviously, we can’t demand a precise explanation of a particular project from everyone, especially the kids. But I think it’s a great pleasure to look at them, their faces flushed with excitement, telling what’s going to happen next in their very own chain Experiment device’, she said.

Original text: www.nauka.uj.edu.pl